For a little over 50 years, video games have been a significant part of popular culture, for millions of people around the world. Born in the minds of creative and curious engineers, games have grown from mere electronic curiosities into a global industry worth billions of dollars.

Blurring the lines between art and interactive entertainment, video games create emotions and experiences like no other product.

Join us as we take a long stroll through 5 decades of video games, reviewing some of the highs and lows, and other key moments in between. While we can’t cover every title released, as even just the best-selling ones would fill several articles, there will be some great ones to reminisce over. Put your devices on mute, grab a favorite beverage, sit back, and enjoy!

Humble beginnings

Because we’re looking at video games for the mass consumer, we can ignore but still pay our respects to the efforts in the 1950s and 60s. One-off creations, such as Bertie the Brain (1950), were created as engineering promotions, and it arguably wasn’t a video game. Spacewar! (1962) certainly was one, but given that it only ran on DEC’s hugely expensive PDP-1 computer, that wasn’t for the masses either.

To really begin our journey across five decades of video games, we must head to the arcade halls and homes of America, circa the early 70s. Electrical engineers Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney created their own version of Spacewar!, called Computer Space (1971), designing it to run on custom hardware, exclusively for arcades (or any establishment that could afford one). While definitely not the first-ever video game, it was certainly the first commercial one.

With the wonder of NASA’s Apollo missions still fresh in the minds of the public, it should come as no surprise that the game involves flying a rocket about space and blowing up UFOs. There are plenty of online emulators for the original hardware — and the majority of the game images you’ll see in this article are from such things — but watching footage from an actual arcade machine is perhaps the best way to experience the game in the same manner that the public did, over 50 years ago…

It looks a lot better than one might expect for the age, but the gameplay (rotate your ship, use a thruster, fire off one missile at a time) is pretty clunky. The average player thought so, too, as the game’s manufacturer, Nutting Associates, was disappointed by the relatively small number of units sold — somewhere in the region of 1,500.

Bushnell and Dabney parted ways with Nutting the following year, renamed their business Atari, and struck a deal with Bally, makers of pinball machines, to develop a new arcade machine.

This was around the same time that Magnavox’s Odyssey, the world’s first home video game console, hit the shelves. For $100 (about $715 in 2023’s dollars), you got a machine that could draw a handful of squares and a single line, two box-shaped controllers, plastic TV screen overlays, and several game cards that would slot into the machine to alter the way the circuits worked.

While the included games were just variants of a handful of the same type (e.g. hockey was just tennis with a different screen overlay), there was enough to entice people to buy it in reasonable numbers. And the success of the Odyssey, along with the popularity of its tennis game, inspired Bushnell and Dabney to make an upgraded clone — and thus, Pong was born (1972).

The Odyssey’s games were very basic, even for the time — no sound effects were offered, and rules and score tracking were down to the players. Pong addressed these and demonstrated some additional designs.

Take the bat, for example — it looks like a contiguous block of pixels but it’s actually split into 8 parts. Each one generates a different angle of return when the ball hits it, giving an additional edge to the gameplay. Other aspects were more down to hardware limitations, such as the fact that the player’s bat is unable to reach the very top and bottom of the screen, but this allowed for a player to get a sneaky shot around their opponent.

By 1974, Atari had sold thousands of Pong arcade cabinets, each one pulling a healthy revenue each day for its respective owner, but delays in getting the system patented meant that straightforward copycats soon flooded the market (one, ironically, came from Nutting Associates).

Over in Japan, Sega and Taito released their own Pong-clones, Pong-Tron and Elepong (both 1973), but the public’s obsession with medal games meant that video games took longer to find any traction in that country.

Atari would eventually respond by developing a home version of Pong in 1975 and initially partnered with Sears for sales and distribution, before releasing one under their own name. It was an instant success, despite being an eye-watering $100 ($556 in 2023’s dollars), and generated $15 million in revenue in the Christmas period alone. While video games were viewed as somewhat of a niche fad, it was very clear that they were extremely lucrative.

The games come out and the money pours in

Atari, Sega, Taito, et al would go on to release new arcade titles that all proved to be smash hits. Gun Fight (1975), Heavyweight Champ, Speed Race, and Breakout (all three 1976) would bring new themes and gameplay to the public, such as PvP shooting or vertical scrolling racing, and all were very popular — manufacturers sold thousands of cabinets worldwide.

The games themselves were, of course, still very basic as hardware restrictions limited what was possible, in terms of visual complexity, speed, and depth of features. But their novelty and cleverly crafted gameplay drew in millions of quarters.

In the late 1970s, no game demonstrated this as much as Taito’s Space Invaders (1978). Over a four-year period, sales in Japan and the US (manufactured in that country by Midway), grossed almost $4 billion dollars.

Even today, game publishers would gladly sell their kidneys to have a single title bring in that kind of money, but in the late 70s/early 80s, it was a history-defining moment.

But there was a good reason for its success — it was, and still is, a great game.

Simple in premise, addictive in nature, people just couldn’t get enough of it. And it opened the floodgates to a whole host of companies desperate for a slice of that gaming expenditure, with numerous home consoles and cheap computers all competing for sales and attention.

Atari’s second console, the VCS (later Atari 2600), was only modestly successful for the first few years it sold but Atari’s fortunes went through the roof when they acquired the rights to produce a version of Taito’s Space Invaders in 1980. That resulted in sales in excess of 2 million units, just for that year alone, and set Atari on the arcade-to-console porting path.

Over in Japan, Nintendo launched its first-ever console, the Color TV-Game (1977), and proved to be immensely popular, though it was never directly sold outside of its home country. But Atari had plenty of US competition — Magnavox, Coleco, and Mattel were all getting in on the act, and the consumer was somewhat spoiled for choice when it came to choosing a home console.

With the average retail price for all these products being around $220 (roughly $1,000 now), and the games costing almost a third of that figure, the fact that they all sold so well demonstrates just how much people wanted to play video games.

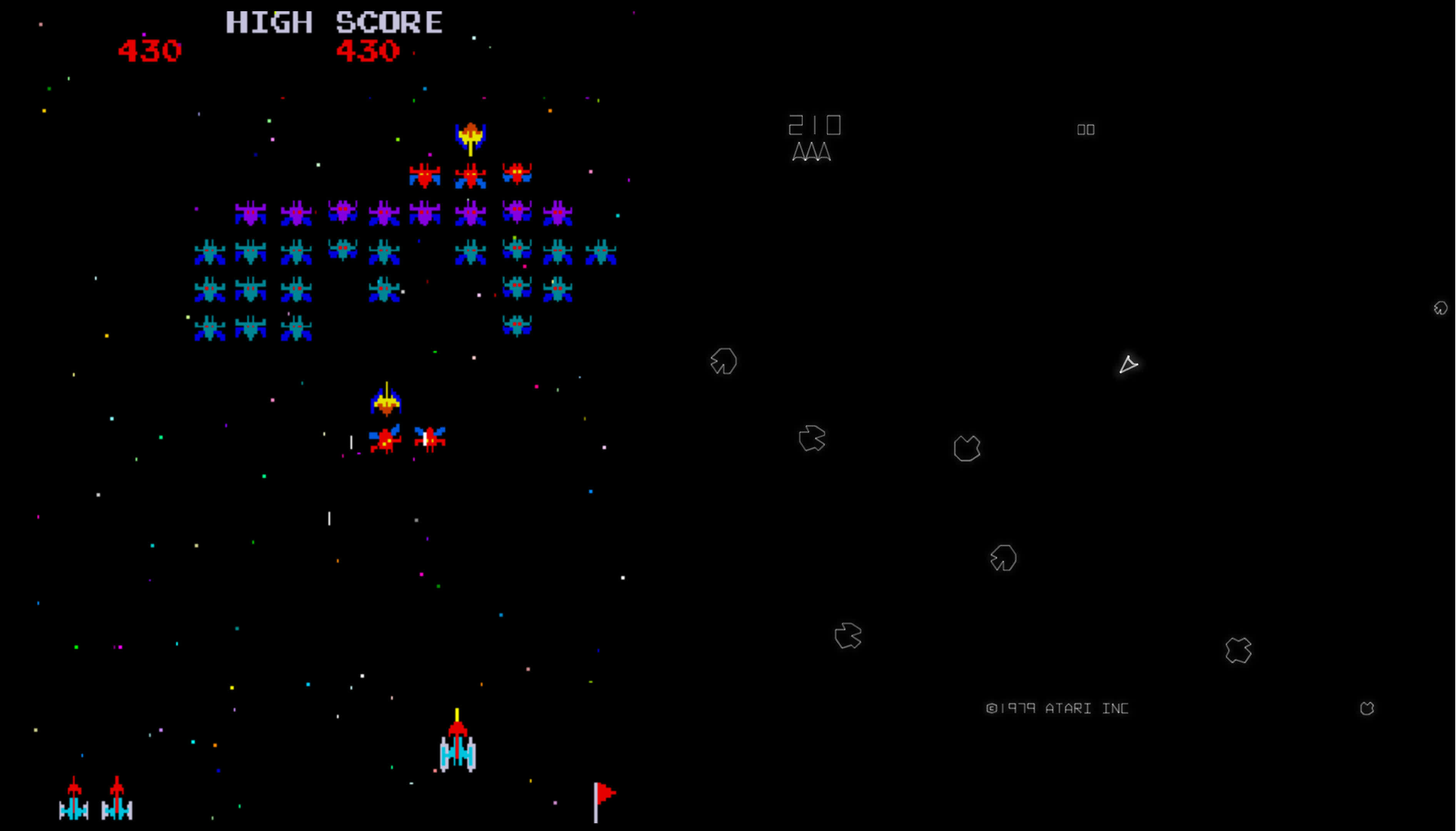

And what games some of them were. Namco’s Galaxian (1979) combined simple but fierce shooting, with glorious color and motion; Atari’s Asteroids took a completely opposite approach that same year, with simple vector graphics and challenging gameplay. And yet, both were lapped up by the public and were eventually ported across numerous platforms, as well as inspiring a raft of clones.

Clones of the top arcade games, licensed and otherwise, all made their way to home consoles and early computers, but not all games of the 70s were about colorful sprites, sound effects, and frantic action. Text-based adventure titles, such as Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), Zork (1977), and Adventureland (1978) would go on to inspire the development of MUD (1978), and the MMORPGs of today can trace their lineage all the way back to these games.

As the decade rolled over, video games were already ingrained into popular culture.

But as the decade rolled over, video games were already ingrained into popular culture. Namco’s Pac-Man (1980), with its basic graphics and sounds, belied a complex structure of carefully honed gameplay and features that would go on to inspire not just endless imitations, but game design in general. Pac-Man was so successful that it went on to spawn an equally-successful animated TV show, as well as sell a colossal amount of merchandise.

It could be argued that it was Pac-Man that started the rise of video game characters being a primary focus of game design — crafted personalities that defined the game’s theme and style. And it was Nintendo who took to this direction most heavily, starting with Donkey Kong in 1981. Arguably the first platformer to include jumping and climbing movements, Donkey Kong boasted features that would become staple fare for countless others, such as cutscenes and different stages to levels (rather than repeating the same scene over and over).

The titular character wasn’t the hero, though — initially, the player’s avatar went unnamed, before Nintendo settled briefly on Jumpman, and finally Mario.

The cap-wearing, mustachioed handyman would return for Mario Bros (1983), cementing the creation as one of the most recognizable names in gaming culture.

Cutting edge to cookie cutter

The main issue that faced companies selling consoles was that they were very expensive for such a singular usage. For example, the Coleco Telstar (1976) retailed at a cent under $100 and offered just three games, all variations of the same theme.

Advances in processor technology were starting to make computers viable purchases for the household, and not just business and industry.

Atari first made use of it in the Atari 400 and 800 (1979), though they came with eye-watering prices — $550 and $1,000 respectively.

Despite this, they sold surprisingly well, simply because there wasn’t much competition, and the platform offered some great games. But where there’s a market, there will always be someone keen to step into it.

Where arcade cabinets cost thousands of dollars to buy and housed custom-designed circuits, the early 80s saw a global rise of their antithesis — the cheap home computer. Powered by simple, off-the-self microprocessors, these devices were mass manufactured and built to be cost effective.

The best-selling examples of such machines were the Commodore 64 and Sinclair’s ZX Spectrum. Polar opposites in terms of price (the former was nearly 4 times more expensive), these computers generally eschewed the use of cartridges and instead loaded games that were shipped on cassette tapes.

While this meant the average load time for a game was 20 to 30 minutes, dispensing with the expensive ROM chips meant that game prices could be slashed. Using this storage medium also meant that people could easily copy and share games, but it also meant that with time, effort, and the right know-how, anyone could make their own game and sell it.

Retailer shelves were packed with ultra-cheap games, though many were utterly terrible, and C64 and Spectrum would eventually go on to boast catalogs of over 10,000 titles apiece.

Since arcade machines were designed to have people constantly adding money to play, the games they offered were constrained by this aspect — short, intense gameplay, was the order of the day, albeit with ever-better graphics and sound.

Home computers were free of this restriction and enabled game developers to become more creative, tapping into uncharted gaming territory. No matter what genre and gaming style you preferred, there were numerous titles to choose from.

In 1984, you could choose between the endless open world in Elite (above, left) to the genre-defining adventure-strategy of Lords of Midnight (above, right), or the anarchic fun to be had with Skool Daze (below, left) to the bizarre comedy in the multimedia oddity of Deus Ex Machina (below, right).

All of these titles, and countless others, were pioneers in this new world and would go on to inspire many of the most popular genres around today.

Some of the biggest game development houses today first cut their teeth on basic home computers. DMA Designs, creators of Grand Theft Auto (1997), comprised young programmers that met regularly at the same computer club.

Some of the biggest hits in this era were designed and coded entirely by one person — River Raid (1982), Jet Set Willy (1984), and Uridium (1986) all demonstrated what was achievable with the right know-how and passion.

While arcade machines and expensive home computers boasted hardware that could handle multiple colors and sprites on screen, there were lots of platforms that were far less capable. Hardware limitations meant game developers had to be as creative as possible to reach their design goals.

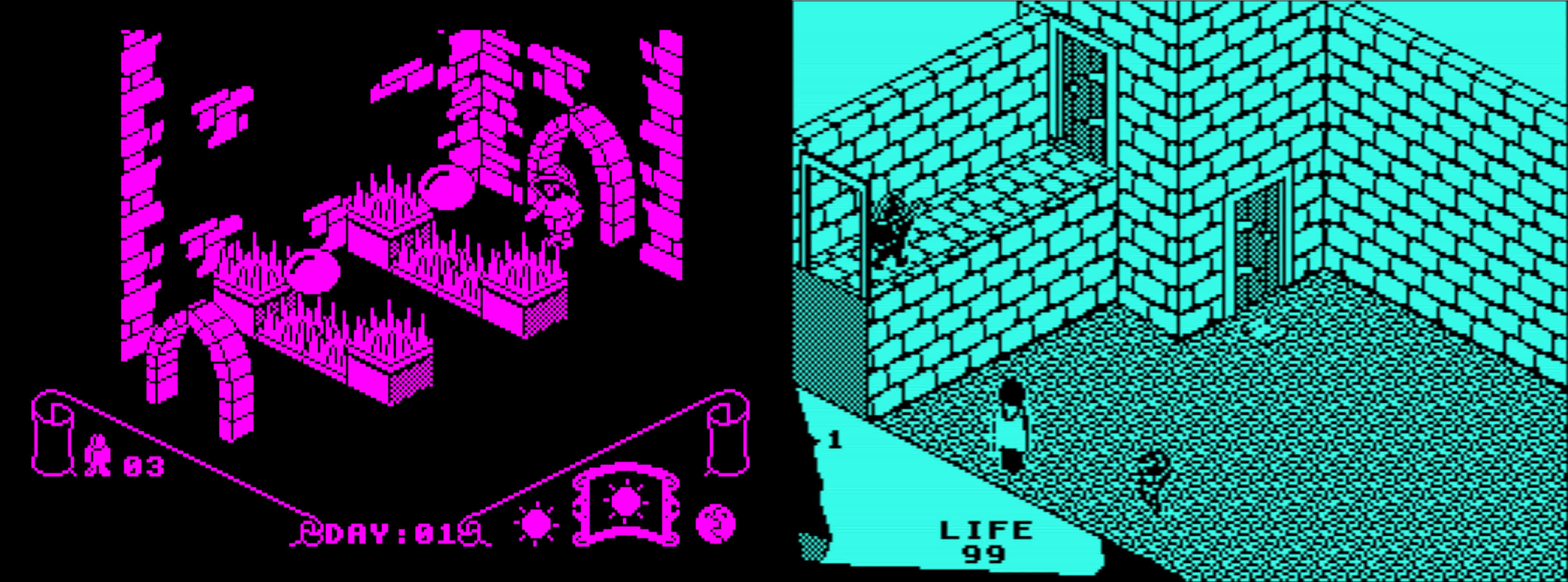

The developers of the hugely successful Knight Lore (1984, above left) turned to the use of masked sprites and a single color to generate its detailed isometric world, and Fairlight (1985, above right) boasted two-channel audio on the ZX Spectrum, despite the fact the hardware didn’t support it. The coders achieved this by alternating between two pitches very rapidly — so quickly that to the ear it sounded like true multi-channel audio.

No game personified this approach better than Tetris (1984). Created entirely by Alexey Pajitnov, initially on a Soviet-era Electronika 60 computer with no real graphics ability, just a text display, the lack of hardware meant that he could focus entirely on honing the gameplay to perfection. The fact that it went on to be the second best-selling title for Nintendo’s Game Boy (1989) and remains immensely popular is a testament to its finely crafted brilliance.

While cheap home computers were very common in Europe, the platform of choice in the US was Nintendo’s redesigned version of their 1983 Famicom system.

At just $180 (equivalent to $500 in 2023), the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was an instant hit. Its hardware was basic but tuned perfectly for games. For five years straight, the best-selling games in the States were all on this platform — the Super Mario Bros series repeatedly outsold everything else by no small margin.

Video gaming seriously faltered in the early/mid 1980s, due to the array of expensive consoles and glut of mediocre titles, but thanks to the 8-bit home computer and the NES, the market recovered quickly and garnered considerable momentum as the decade drew to a close.

Fierce competition between NEC, Nintendo, Phillips, and Sega in the console market, and Atari and Amiga in home computers, would bring superior computing power and graphics to the general consumer. Arcade machines were still the cream of the crop, but gamers at home weren’t going to be disappointed.

Sixteen is the magic number

In 1985, Atari introduced its next lineup of home computers, starting with the Atari ST ($1,000 with a color monitor). Commodore followed suit with the Amiga 1000 in the same year, but that was even more expensive — $1,285 was a huge amount of money, although the machine did sport some of the best hardware you could get at the time.

These machines sported components far better than the previous generation (32-bit CPUs with a 16-bit address bus) and packed considerably more RAM. The graphics output was still relatively basic though.

Both the ST and A1000 could only display a limited number of colors on-screen at the same time, and from relatively small color palettes (9 bits and 12 bits, respectively). This didn’t stop developers from creating some standout games for both computers, though.

Although early releases in the platforms’ large catalog of titles were mostly arcade ports and upgraded versions of older games, Dungeon Master (1987) brought real-time battles and an active experience point system to the RPG genre, and the likes of Starglider 2 (1988, above left) and Stunt Car Racer (1989, above right) wowed reviewers with flat-shaded polygons.

Arcade machines in the mid-1980s had also moved on to sporting complex hardware that used full 16-bit palettes, although such systems were five times more expensive than those home computers. One of the first games to utilize the better graphics technology on offer was Sega’s Space Harrier (1985). While nothing more than an ‘on rails shooter’, it was frantic, colorful, and hugely popular around the globe.

Meanwhile, since the majority of the gaming market still only had 8-bit consoles and home computers, they had to make do with pared-down ports of the top arcade hits, such as Commando, Ghosts ‘n’ Goblins, and Paperboy (all 1985). The gameplay generally remained intact during the coding transfer, but the visuals were nearly always notably downgraded.

Not that this mattered much, as there was an astonishing array of original titles that made the best of the machines they ran on. Action-adventure tiles like Metal Gear (1987, below left), rewrote the RPG template where story and exploration, rather than loot and experience points, became the central focus.

And developers of Driller (1987, above right) performed amazing feats of coding, offering pseudo-shaded 3D graphics on machines that were barely rendering a handful of sprites a few years ago.

Towards the end of the 1980s, the video game industry had fully bounced back, thanks to the millions of consoles and computers in homes around the world. American and Japanese manufacturers deemed that the time was ripe for new machines that could run games with graphics like those found in arcade halls, but without the extremely high price tags that the Atari ST and Amiga 1000 proudly wore.

Between 1987 and 1991, four new consoles hit the shelves, all boasting the “16-bit” moniker in one form or another: NEC TurboGrafx-16, Sega Mega Drive/Genesis, Nintendo Super NES (SNES), and SNK’s Neo Geo. However, only the Neo Geo offered full 16 bit graphics ability, though the SNES was pretty close; NEC’s offering was ostensibly still an 8-bit console.

Even so, the new machines blew away the old guard in speed and capability, and the first games took advantage of the better hardware in terms of graphics and sound. Game design, though, was still much of the same fare that had been served for the past decade — arcade hack ‘n’ slash or scrolling beat ’em ups were almost ubiquitous.

When Sega launched the Mega Drive in the US (known as the Sega Genesis), the six launch titles comprised one sports game and the rest were the likes of Altered Beast, Golden Axe (below), and Space Harrier II.

Arcade-style games were Sega’s forte, of course, and not all of the new releases followed this route. Nintendo included SimCity and Pilot Wings with the North American launch of the SNES — the latter game was a simplified flight simulator that was used to highlight the console’s graphical abilities.

Part of the reason why so many games were either arcade ports or clones was that semiconductor components such as ROM and RAM were still hugely expensive, and with the consoles still using cartridges to store all of the game’s assets, they were limited in their scope.

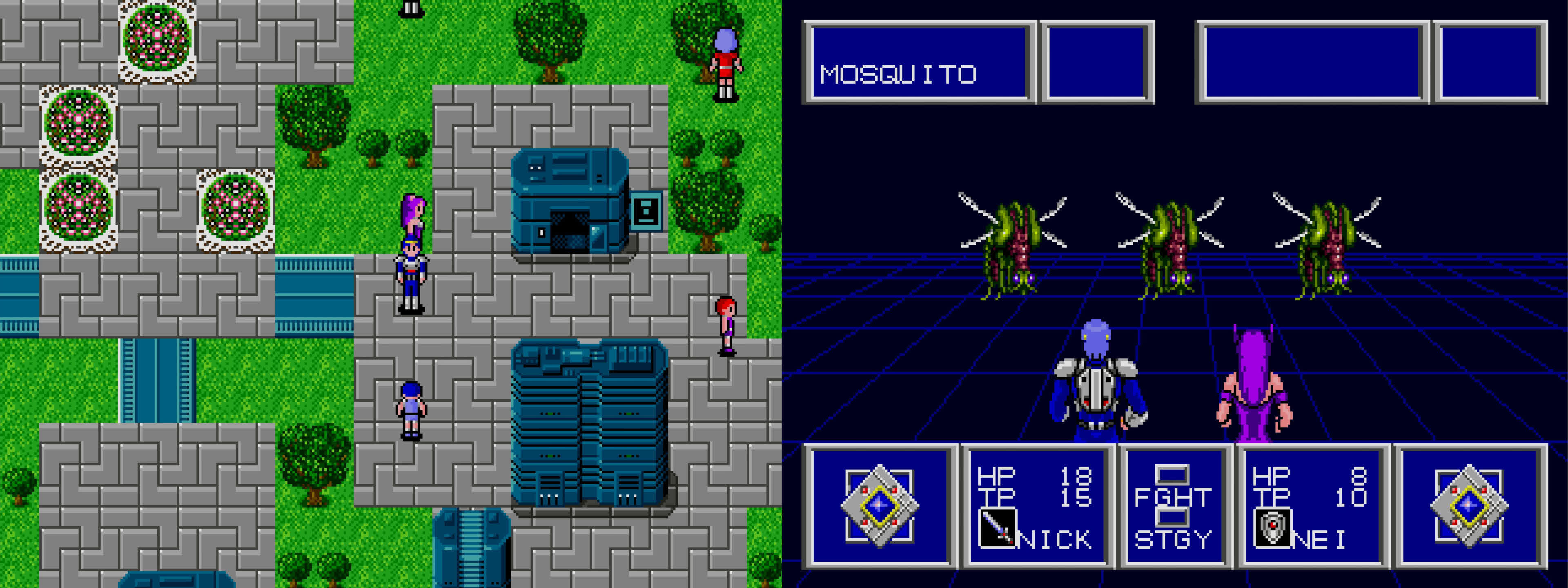

Fortunately, there were some developers who refused to follow the crowd. The seminal Phantasy Star II (1989, below) for the Mega Drive/Genesis was colossal in size, with its 6 Mbit ROM being larger than anything else at that time. The RPG, with turn-based combat, combined a multitude of gameplay elements that are still in use today.

The older machines weren’t being ignored, either. With tens of millions of homes in North America, Europe, and Japan owning at least one 8-bit or 16-bit machine, there was a huge market to cater for.

God game Populous (1989) was released on the Amiga 1000 before being ported to multiple platforms and proved to be an instant hit. Prince of Persia, released in the same year, wasn’t commercially successful to begin with, as it was launched on the Apple II — its storytelling and animation, though, were exceptional and later versions for older machines sold well.

With great power comes great games

What all of the game publishers really wanted, though, was another Space Invaders or Pac-Man — something that would become a cultural phenomenon and rake in the cash, through merchandise and other tie-ins. For Nintendo, this was Mario, of course, and Super Mario Bros 2 was the top-selling title in the US for almost the entirety of 1989.

Sega followed suit two years later with Sonic the Hedgehog (1991, below), a game deliberately created to beat Nintendo at its own game, so to speak.

What Super Mario Bros did for the NES, Sonic repeated for the Genesis, and it helped cement the platform in the North American market before the international release of the SNES.

Such were the sales of Nintendo and Sega’s consoles that NEC and SNK couldn’t compete, although the latter’s extremely high price ($650 for the console, two joysticks, and one game) didn’t help.

Other titles released at the time didn’t do wonders for the shipping figures of computers and consoles, nor expand the depth and range of video game design, but they kickstarted new franchises for people to clamor for, such as Streets of Rage, Road Rash, and Shining in the Darkness (all 1991).

But this was also the era of sequelitis and it was rare for arcade machines and consoles to sport something fresh and new. You needed to look at other platforms for gaming innovation.

Initially released for the Amiga, Lemmings (1991, above) was perhaps the best example of this — as an almost lone puzzle/strategy game standing in the midst of countless shooting, racing, and platformer titles, it’s a tribute to its brilliance that it sold so well.

When it came to finding games that did their own thing, rather than aim at the masses, the platform that probably had the best of them was the IBM PC-compatible computer. The machines were hugely expensive, as well as fiddly to use and configure, but had notably increased in popularity as home game machines in the early 90s.

The Secret of Monkey Island (1990), Wing Commander (1990), Civilization (1991), and Alone in the Dark (1992) can all be considered the most outstanding examples of what could be achieved on the PC, for the period.

Be it through finely crafted gameplay, professionally acted cutscenes, or creating entirely new genres, these titles marked a key change in how games were being made.

As the 90s progressed, developers began to fully explore what consoles and computers were truly capable of, and games started to show more complex design and programming. Just as in the era of the cheap 8-bit home computer, creators weren’t asking what they could do on a given machine, but instead took their design briefs and say ‘we’ll make this work, no matter what.’

F-Zero (1990) and Super Mario Kart (1992) made full use of the Mode 7 rendering feature, giving the racing genre a healthy dose of modernization, thanks to its pseudo-3D graphics. Wolfenstein 3D (1992) was a breath of fresh air on the PC, with its visceral gameplay unhindered by the basic-looking faux 3D rendering. This title gave rise to the seminal Doom (1993) — a landmark game in terms of popularity, impact on the industry, and technical prowess.

It wasn’t always about fancy graphics, though — the soundtrack to Secret of Mana (1993, below) was second only to the game’s beautifully crafted sprites. Nintendo’s SNES arguably had the best audio capabilities of all the consoles in this era, but few games utilized it as well as this one.

But waiting just around the corner was something special — not just amazing new titles, pushing the limits of what was considered possible on the hardware, but a whole new paradigm for consoles, computers, and video gaming to follow.

It would come to define how games would look and what levels of creativity were possible. It would bring a new adversary into the gaming arena, revolutionize a storage medium, and target a neglected demographic of video game players. This time, there would be two magic numbers and both would have 3 in them.

———-

In Part Two, we’ll see how games evolved through the rest of the 1990s and through the early years of the new millennium. New technologies would not only alter the way games look and feel, but how we play them, individually and together. Stay tuned for that.