In Part Two of our journey through the history of video games, we saw the rise of 3D graphics and how that introduced a raft of new genres and gameplay modes. By the turn of the new millennium, both consoles and gaming PCs showcased incredible titles featuring rich stories, cinematic action sequences, and stirring musical scores.

While the stalwarts like Nintendo and Sega continued to cater to their traditional markets and franchises, newcomers Microsoft and Sony presented their gaming worlds to a broader, more mature audience, and many of their games reflected this shift.

Where the old guard of Nintendo and Sega still favored their usual markets and franchises, newcomers Microsoft and Sony offered their worlds of gaming to a wider, more mature audience and many games reflected this.

Compared to previous decades, an ever-increasing number of people were spending more of their hard-earned cash on the latest technology and services. In an industry with few competitors, corporate leaders grappled with the challenges of expanding into new arenas while ensuring growth in established sectors.

As history showed, advances in technology once again paved the way for new opportunities.

TechSpot’s 50 Years of Video Games

TechSpot’s 50 Years of Video Games

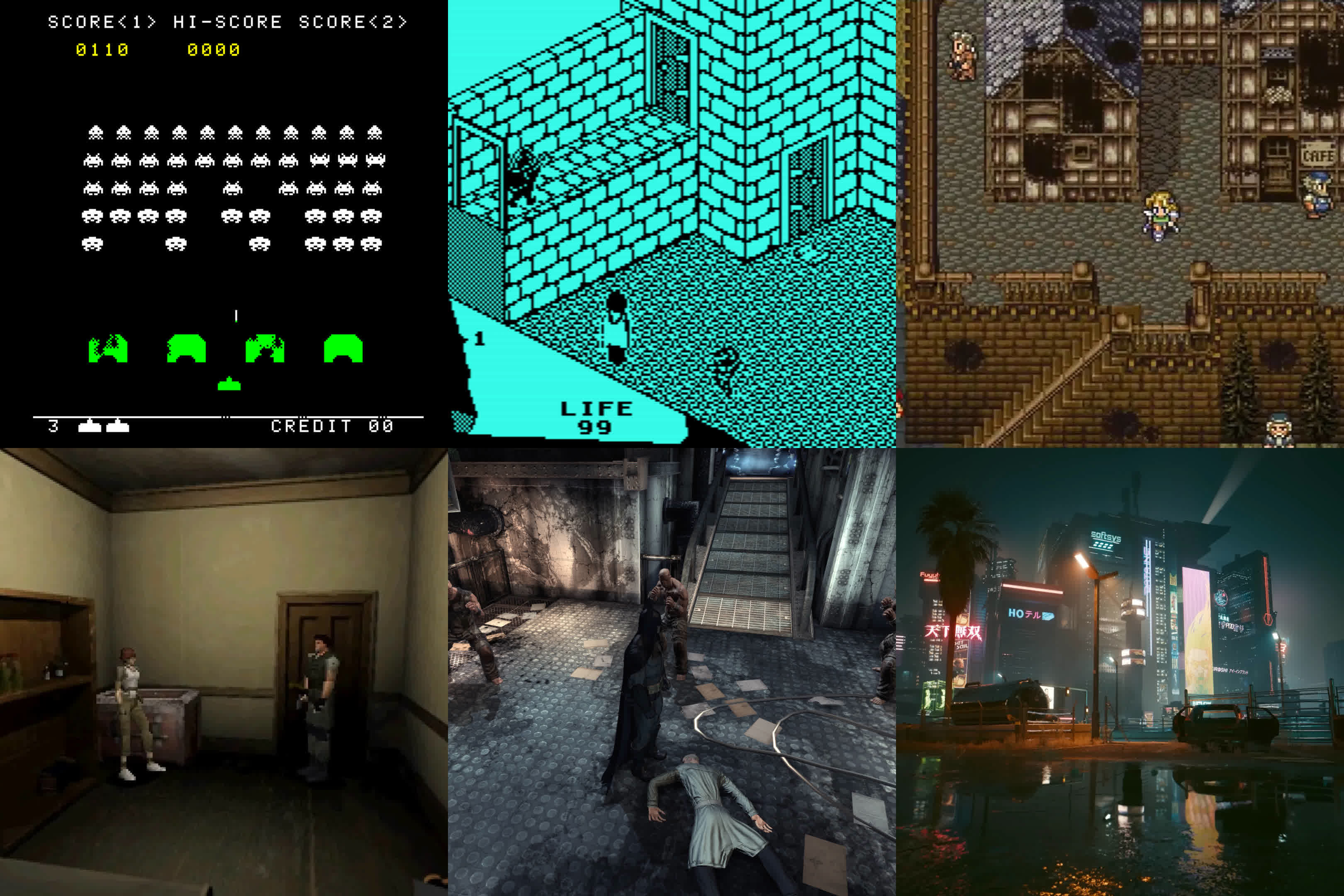

For over 50 years, video games have been a significant part of popular culture. Born in the minds of creative engineers, games have grown from mere curiosities into a global industry worth billions of dollars.

A decade of expensive excellence

With the release of Microsoft’s Xbox 360 in 2005, both major players in the console market had machines equipped with DVD-ROM players. A year later, Sony unveiled the PlayStation 3, which included a built-in Blu-ray player supporting 25 to 50 GB discs. Though ambitious, no games approached using the full capacity at that time.

Worth noting, the PS3 significantly contributed to the triumph of Blu-ray over HD-DVD, given that the console was priced considerably lower than standalone Blu-ray players.

The vastly superior hardware in consoles and gaming PCs, combined with generous storage formats, granted developers unparalleled freedom in terms of game size, scope, and graphical integrity.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006, below) and Grand Theft Auto IV (2008) were two perfect examples of how bigger budgets, more capable chips, and extensive data storage could be harnessed to craft games of epic proportions.

Between 2002 and 2009, console and PC owners were treated to some truly outstanding titles. More than merely being excellent games, they were profoundly influential, setting standards in themes, gameplay styles, and features that would be emulated for years.

The tense action and fluid combat system in Batman: Arkham Asylum (2009) became a benchmark for third-person action games. Virtually any contemporary single-player action-adventure draws inspiration from the narrative techniques in Half-Life 2 (2004), Mass Effect and BioShock (both 2007), intentionally or otherwise.

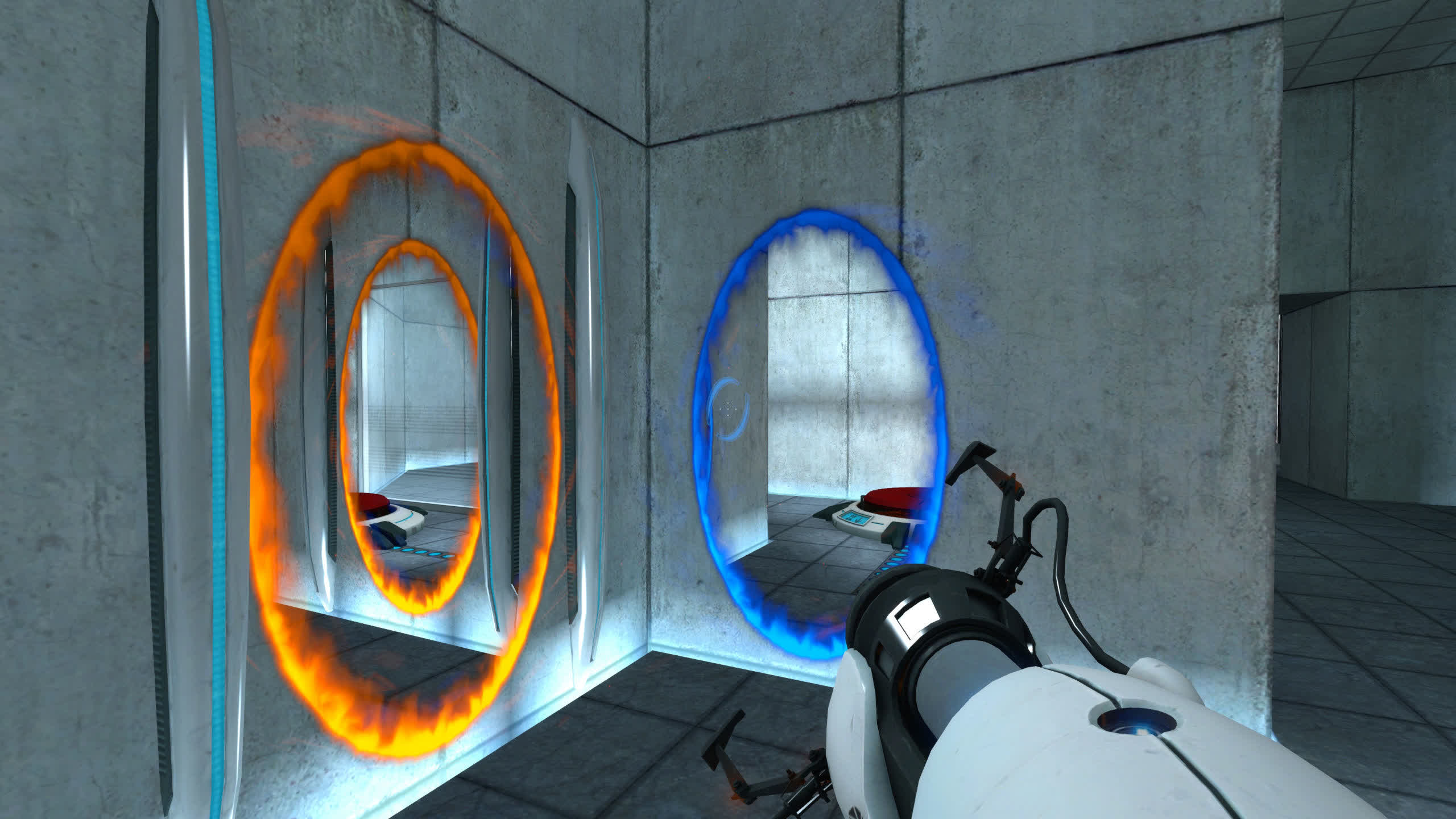

Though disparate in style, Super Mario Galaxy (2007) and Portal (2007, below) established production standards we would soon expect from premier publishers.

Team Fortress 2, part of Valve’s 2007 Orange Box collection (which included Half-Life 2, its two episodic expansions, and Portal), raised the bar for multiplayer FPS games to a height unmatched for years. Similarly, the graphical prowess of Crysis (2007) was unparalleled.

This era witnessed gaming budgets comparable to those in the blockbuster film industry. While iconic titles like Final Fantasy VII had hefty development costs, around $40 million, such figures were becoming standard. Half-Life 2 and Halo 2 (2004) had budgets comparable to SquareSoft’s legendary RPG, despite being primarily linear shooters showcasing advanced graphics and tech.

Investors, however, grew cautious about allocating enormous funds to single titles. Licensing for music or brand tie-ins proved particularly expensive, and while cutting-edge hardware could render breathtaking visuals, game development became increasingly intricate and prolonged.

Thus, the era of AAA franchises dawned. Games like Assassin’s Creed (2007, above) transformed into lucrative behemoths, with IPs or technologies exploited annually. While the gaming market was no stranger to spin-offs and derivative releases, the primary motive shifted from sales-driven decisions to the necessity of recovering substantial initial outlays.

Few franchises epitomize this trend better than Activision’s WWII-centric Call of Duty. Debuting in 2003, it was developed by a modest team at Infinity Ward, predominantly former developers from the Medal of Honor series.

With a modest budget of $4.5 million, the game’s success, while commendable, didn’t top charts. However, the series’ trajectory shifted with Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare (above), propelling it to iconic status with a legacy spanning two decades and over 30 titles across all platforms under the Call of Duty banner.

Yet, not everything in this decade revolved around exorbitant budgets, cinematic spectacle, and visual marvels.

Simple still sells well

Having lost the battle for the top slot in console sales, Nintendo charted a different course from Microsoft and Sony for its successor to the somewhat lackluster GameCube. While the Xbox 360 and PS3 flaunted cutting-edge technology and immense computing power, Nintendo’s new machine would be more straightforward, though with an innovative twist.

Released in 2006, Nintendo’s Wii was an overwhelming success, despite the mixture of praise and criticism the hardware contained inside the case. The unique selling point didn’t come in the form of embedded DRAM or multicore vector processors – it was a controller, or rather, how it could be used.

Eschewing joysticks and fancy triggers, Nintendo developed a clever motion-tracking system that enabled players to interact with a game simply by moving the whole thing about.

But the true killer feature in the Wii was its game library and broad appeal. In 2007, Nintendo secured four slots in the top 10 best-selling games of the year (plus another two for their portable Nintendo DS system), with Wii Sports alone moving over 15 million copies. This game would continue to top the charts for an additional two years, and Wii titles in general largely dominated the market, buoyed by the console’s vast popular appeal.

While the Xbox and PlayStation catered primarily to teenagers and young adults, the Wii and its game roster attracted a far more diverse audience. Nintendo’s console could be spotted in homes, hospitals, schools, and even offices worldwide, usually with Wii Sports or Wii Party as the primary discs in rotation.

However, the Wii’s success wasn’t the sole shock of the decade. Despite being classified as a mere rhythm game, Guitar Hero (2005) won over both critics and players. While its initial sales were solid, if not spectacular, they sufficed to guarantee a slew of sequels and specialized versions over the next five years, not to mention the inevitable surge of imitations and direct clones.

Guitar Hero’s popularity was explained by a number of factors, but once again, the controller was that magic touch.

Instead of using the standard PS2 gamepad, the game came with a dedicated miniature guitar, sporting colored buttons that the player would press in time with those shown on the screen, along with a paddle to simulate strumming, and a whammy bar for changing the note pitch. Despite the cheap toy appearance, the controller made all the difference – it elevated the game’s simple mechanics into something far more tangible and relatable.

Even simpler games

The continued growth of the Internet and the expansion of high-speed connections opened up a new market for simple games. In 2005, Adobe bought another organization in the same field, Macromedia. With the purchase, the company got its hands on several well-known packages, such as Dreamweaver, Shockwave, and Fireworks.

Alongside these came Flash, a platform that could be used to stream video and audio clips, and create animations and even simple games. The tools were easy to learn and in the case of the latter, anyone could play such creations if they had the Flash Player program installed on their computers.

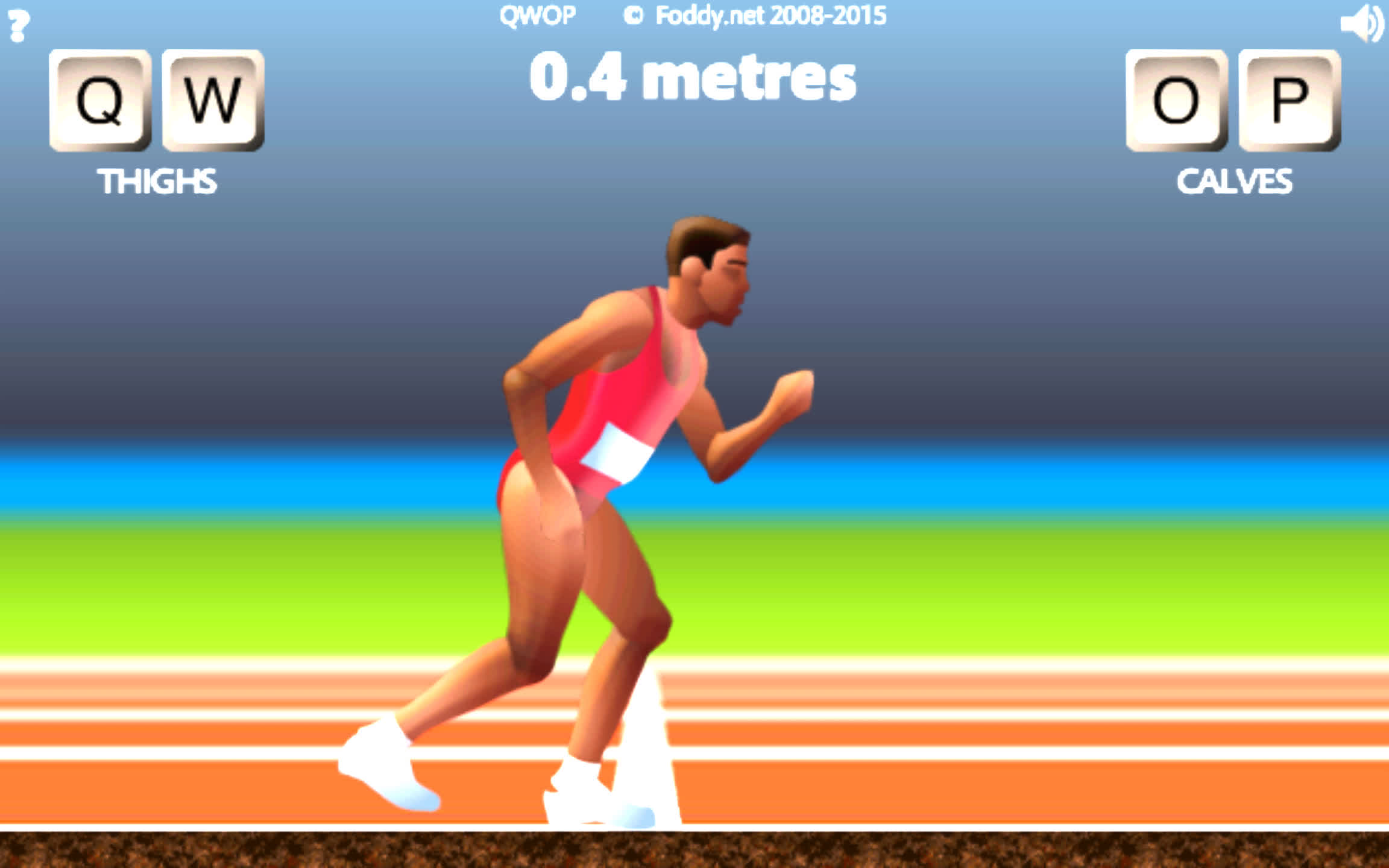

And so web browser casual gaming became the “next big thing” – created using the likes of Java or Flash, hundreds of millions of people became addicted to Bejeweled (above), Crush the Castle, QWOP (below), FarmVille, and countless others.

More serious games pursued alternative avenues to reach global audiences. Microsoft’s Xbox Live Arcade served as a digital platform for smaller, independent developers. Additionally, the rise of early access versions of games offered both a source of revenue and a means for quality testing, even for titles created by just one or two individuals.

Perhaps the most iconic of these is Minecraft (2009). Starting as a solo endeavor by Markus Persson, it was initially released to the public via discussion boards. By 2011, the game’s development had transitioned to a small yet dedicated team under the company name Mojang. Remarkably, it had already surpassed a million copies in sales – all without a publisher, virtually no marketing apart from word-of-mouth, and while the game remained in a relatively rudimentary beta stage.

Affordable and fast internet access also aided the growth of the MMO genre (massively multiplayer online), especially role-playing titles. RuneScape (2001), Second Life (2003), World of Warcraft (2004, below), and The Lord of the Rings Online (2007) would all become incredibly popular and their subscription model of revenue would draw in millions of dollars each year.

At its peak, the World of Warcraft had an estimated 12 to 15 million players across the globe, and all four titles still have a large number of active players. But as the years rolled into another decade, a new force would rise up and come to dominate them all, in terms of player count, popularity, and money-making ability.

Gamers on the go, greed by the billion

For as long as video games have existed, there have been electronic devices enabling players to enjoy gaming on the go. Early systems offered just a single game, such as Tic-Tac-Toe, but the first to feature swappable games was Milton-Bradley’s Microvision. Launched in 1979 at a relatively steep price of $50, the system boasted a catalog of 12 titles, all displayed on a modest 16 x 16 pixel LCD screen.

Nintendo introduced a similar concept, minus the ability to change games, with its Game & Watch series. The first, titled Ball, debuted in 1980. Being a rudimentary ball-juggling game, it didn’t achieve blockbuster sales. However, everything changed when Nintendo began incorporating its more renowned IPs into the platform. The dual-screen Donkey Kong Game & Watch, released in 1982, sold over 8 million units worldwide.

The Japanese giant would later transform the portable gaming landscape with the Game Boy in 1989. While Atari and Sega introduced their own handheld devices (the Lynx and Game Gear, respectively), they couldn’t challenge Nintendo’s stronghold despite their superior graphics and processing prowess.

For decades, if one sought a mix of well-designed games, from simple platformers to intricate RPGs, the go-to device was either the Game Boy or its later successor, the DS (2004).

Even Sony, wielding its robust PlayStation Portable (2004), struggled to carve a significant niche in this market. A notable attempt at change was the Nokia N-Gage in 2003. This combination of mobile phone and handheld console, aimed at leveraging Nokia’s vast user base to compete with Nintendo, sadly missed its mark.

Despite the everyday popularity of games like Snake and Bounce on Nokia phones, the N-Gage’s awkward design and tiny screen deterred many. Those who played games on their phones typically favored minimal controls and straightforward gameplay.

Apple unveiled the first iPhone in 2007 and in the following year the company introduced the App Store. While neither the first ‘smartphone’ nor the pioneer of digital distribution platforms, Apple’s ecosystem was widely adopted by third-party developers and brought in huge sums of money for the company. It also helped the mobile phone to eventually become the most popular gaming system in the world.

Although early mobile games were nothing special, their affordability and accessibility, coupled with a quick development turnaround, made them attractive. The marketing and monetization strategies for these titles shifted significantly when Apple, among others, endorsed in-app purchases (often termed microtransactions). This ushered in the era of the “freemium” revenue model: offer the game for free, but embed incentives for players to spend on in-game consumables.

Within a few years, games with the largest player bases and highest revenues predominantly embraced this freemium approach. Titles like Puzzle & Dragons, Clash of Clans, Roblox, and Candy Crush Saga, all launched in 2012, each amassed cumulative revenues surpassing $4 billion.

Not every success followed that model, though – Rovio Software’s smash hit Angry Birds (2009, above) topped the charts even though it had a small price tag. Naturally, microtransactions eventually made their way into the long-running series of bird-vs-pig puzzle games. They also made their way onto other platforms.

Paying a small fee to have an extra feature or cosmetic item in a game had been around for some time, but it was Microsoft that really pushed its use with the paid-for-points system on Xbox Live (discontinued in 2013). Its online marketplace overflowed with downloadable content (DLC) for various games – some complimentary, most not. One of the most infamous examples of this was a set of horse armor for The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion.

For $2.50 one could furnish your in-game mode of transport with a golden set of armor plating that did absolutely nothing, other than make the horse look so garish that had the game sported aircraft, the pilots would have been blinded constantly by the radiating glare.

Soon, most AAA franchise titles adopted a similar approach. The game development paradigm evolved into a continuous online service, ever-pushing maps and cosmetic DLCs for continued revenue.

Top game publishers like Take 2, Ubisoft, and EA fully embraced this model and presently a significant portion of their revenue stems from microtransactions. Games, particularly those with multiplayer modes, bore the brunt of this lust for revenue. Franchises initially celebrated for their single-player experiences, such as Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto, would go on to all but abandon their roots to feast on the gaming-as-a-service fruit.

Good games always prevail

With billions of dollars potentially at stake, you might assume that every publisher would eagerly jump onto the DLC/content monetization bandwagon. Thankfully, this wasn’t the case for the most part.

In a decade that threatened to see the entire gaming industry transform detrimentally, many of the top-selling titles were either purely single-player or featured a multiplayer mode that didn’t prioritize squeezing last dime from players. And it started oh-so-well – Super Mario Galaxy 2, Red Dead Redemption (below), Mass Effect 2, StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty, and Halo: Reach (all 2010) were all outstanding examples of game devs at their very best.

The fact that most of these were sequels or franchise segments of some kind just didn’t matter and the following year was no different, with Batman: Arkham City, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Portal 2, and The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword all being utterly fabulous.

While 2012 had fewer notable releases, games like Far Cry 3, Dishonored, Mass Effect 3, Borderlands 2, and XCOM: Enemy Unknown compensated.

With the release of Microsoft’s Xbox One and Sony’s PlayStation 4 in 2013, consoles gained the processing prowess to elevate games to new cinematic heights. Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us beautifully exemplified what could be achieved with the right amount of time, talent, and resources.

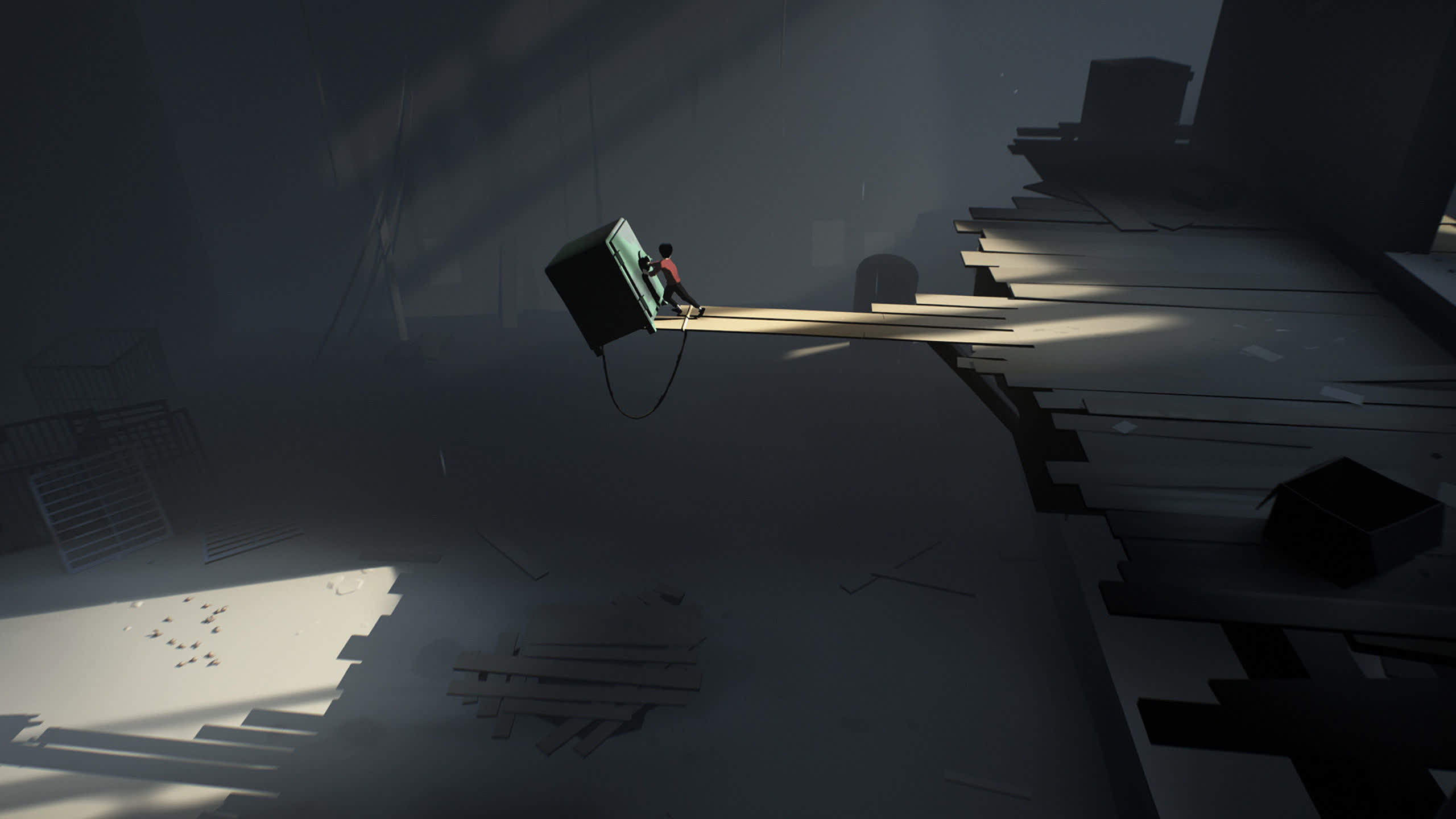

Over the following years, games like The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015) and Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018) pushed boundaries. Meanwhile, smaller projects such as Undertale (2015), Stardew Valley (2016), and Inside shone brightly despite their modest origins.

However, the past decade in gaming hasn’t been without challenges. With widespread fast internet access, publishers gravitated toward digital distribution, particularly for PCs, reducing second-hand sales and prompting a higher use of DRM (digital rights management).

Ubisoft and Electronic Arts introduced Steam-like platforms to maximize profit margins, while Epic Games launched a direct competitor to Steam, boasting lower fees and periodic free game offers.

The pressure on development teams to incorporate additional paid content or span multiple platforms added to the already daunting task of creating modern AAA games. Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) is a prime example of these challenges, facing significant issues, especially on PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, which took over a year to rectify.

This became an unfortunate but common theme for PC versions of big-budget titles primarily made for the latest consoles – on release, the performance would be shockingly bad, only to be fixed after many months of updates. Apologies would be issued, but with the initial sales always reaching expectations, there was no financial incentive for publishers to do something different about it.

Freemium mobile games, DLCs, and season pass add-ons still dominate revenue streams. However, a remarkable game always stands out. Notably, no skin pack, with perhaps the exception of Oblivion’s infamous horse armor, will ever be immortalized in gaming history. This observation isn’t a critique of player preferences; it merely emphasizes that the games we’ve discussed throughout this series left lasting impressions because of the joy and wonder they inspired.

Gaming technology keeps advancing at an impressive rate. Current consoles from Microsoft and Sony significantly outpace their predecessors, as do the latest computer graphics cards and CPUs.

Some technologies enjoy brief popularity before fading and being replaced. For instance, virtual reality headsets have succeeded motion-tracking sensors, while various cloud gaming services have emerged and disappeared. But a great game is remembered, respected, and admired despite the tech it uses, not because of it.

The true essence of a great game transcends its technology.

Once deemed a fleeting pastime for a niche audience, gaming is now as mainstream as watching TV. It’s an entertainment and sport embraced by all, irrespective of age, gender, or background. Estimates suggest over 40% of the global population engages in some form of gaming.

The exact number of games developed and released globally in the past 50 years might be incalculable, but it’s likely in the millions.

Paying tribute to all of the great titles ever played is beyond the scope of this series, or the work of any single publication. But it doesn’t really matter – the memories they’ve given us provide a far richer testimony than mere words and pictures.

Video games may only be half a century old – a mere child compared to television, film, and radio – but this young industry has shown it’s no mere pale imitation of them; it is an equal among giants. We may not yet fully recognize or appreciate it, but the history of video games is a record of history itself.